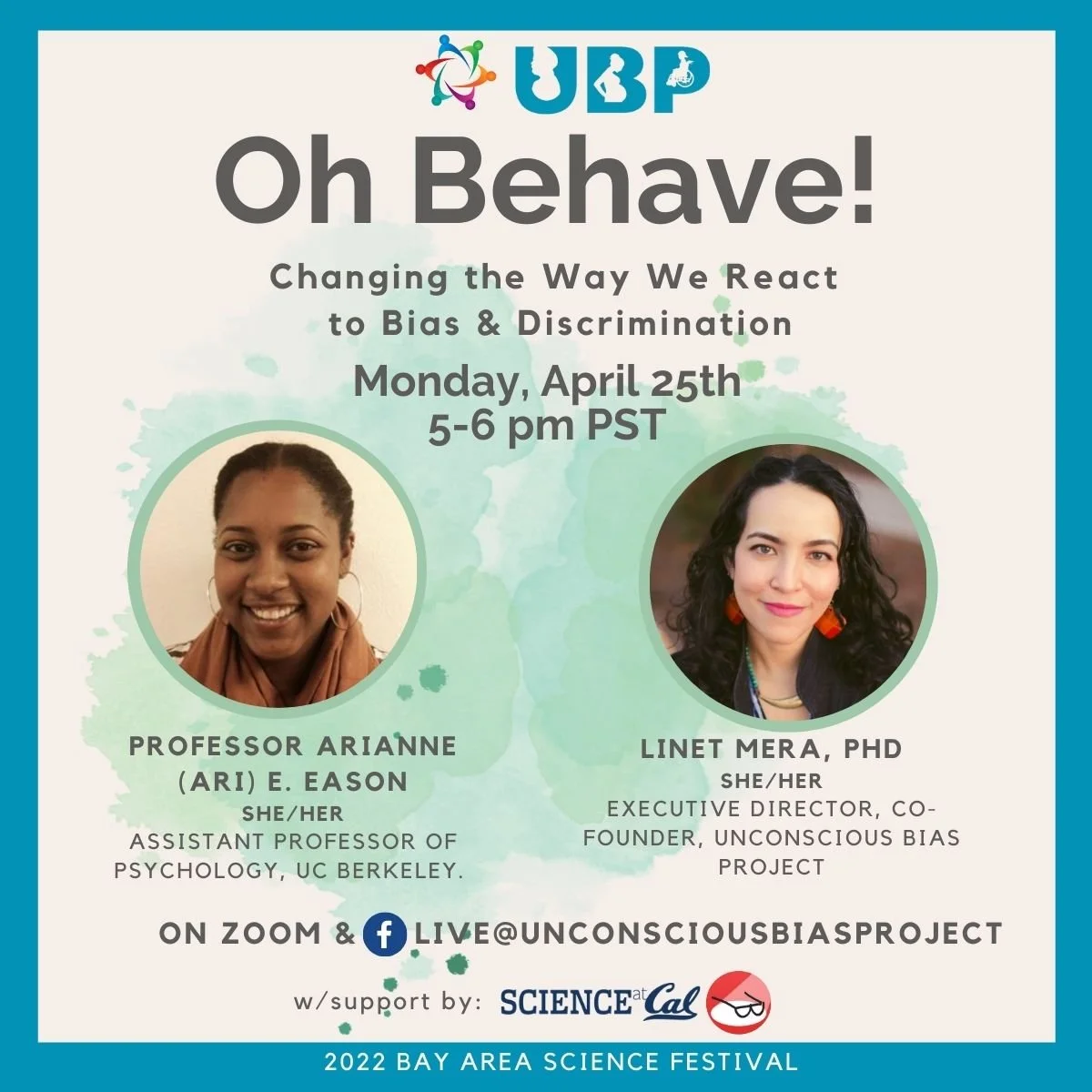

Oh Behave!

Changing the Way We React to Bias & Discrimination

Published on: March 3, 2022. Updated: May 18, 2022

Can we really tackle bias and discrimination?

Join us April 25th 5:00 - 6:00 pm PST for a virtual workshop as part of the Bay Area Science Festival!

Dive into the research with Asst. Professor Eason, UC Berkeley Psychologist, to demystify why prejudice and bias have persisted for so long. Understand the impacts of our “representational landscapes”, such as why folks like Native Americans and queer people get left out of our national narratives or how the presence of racial segregation maintains bias, and what actions we can take against it.

Then take some tools to that noggin’ with science-tested practical techniques by the Unconscious Bias Project with Dr. Linet Mera that you can apply in seconds to fight discrimination when it comes up and when you see it happen in real life.

Talk to the experts and learn practical tools you can apply any time to *actually* make the world a better place.

Bring pen and paper to follow along in our livestream or get ready to participate in our small group event by registering via Zoom.

Our Speakers

Dr. Arianne E Eason, UC Berkeley

Dr. Linet Mera, Unconscious Bias Project

Dr. Arianne (Ari) E Eason (she/her) - Dr. Eason is an Assistant Professor at UC Berkeley’s Department of Psychology where she works to understand how features of our social and cultural context shape peoples’ attitudes and behavior in ways that work to reinforce existing inequalities and stagnate change. Her work aims to shed light on: 1) how we think about and behave towards diverse others within a complex society riddled with inequality; and 2) how we facilitate positive change.

Dr. Linet Mera (she/her) - Dr. Mera is co-founder and co-Executive Director at Bay Area’s Unconscious Bias Project (UBP), a people & culture nonprofit consultancy. She is a Colombian-American Latin@ scientist with indigenous heritage that wants to bring the message “inclusion is a choice” to the world through practical actions and empowering programs to help foster inclusion and equity in our diverse workplaces and classrooms. Connect with her @LinetMera on Twitter or on LinkedIn

Accessibility

We want everyone to feel welcome to join our event. We will have an ASL interpreter and Otter.ai live transcription for anyone that needs it. If you have other accessibility needs or want to be connected directly to our interpreter, let us know in the registration form or by emailing us at ubp@ubproject.org.

Thank You

We thank our Awesome Anonymous Sponsor for helping us provide ASL interpretation at our event and to Nerd Nite SF for sponsoring our new cartoon by Theresa Oborn.

We are grateful for the awesome support including feedback, connection with Professor Eason, and event boosting by Nerd Nite SF & Science at Cal - You rock!

2022 Bay Area Science Festival

”Oh Behave!” is part of the 2022 Bay Area Science Festival (4/11 - 4/30) with virtual and in-person events for families, youth, and adults to experience the world of science with STEM role models. Learn more about the festival at BayAreaScienceFestival.org.

Would you like to sponsor this event?

Email us at ubp@ubproject.org to find out how you can make an impact at any level and receive a shoutout during our event. To support this event and all our projects, click this donation link.

Transcript

Linet 00:02

Okay, great. Susanna, please let folks in from the waiting room Great. Hi, everybody. Welcome. Welcome. Thanks for joining. Hey, everybody. Hi. So nice to see you. Thank you for joining. How's everybody doing today? Oh, good. I see folks starting to fill out the poll. Please do, we have a poll in the Zoom that will feed into something that we'll be talking about really soon. Okay, and now we have the live-stream set up. So we will start really shortly. Hi. We're doing great. Thank you for joining us. Okay, so the folks that are just joining us right now, let me tell you a little bit about who is in the room. There's myself, Dr. Linet Mera, co-Executive Director of the Unconscious Bias Project. And there's our collaborator, Assistant Professor Ari Eason from the University of California Berkeley. We also have our wonderful ASL interpreter, Shari. Hi, Shari, and our volunteer, Susanna, that's helping us with the waiting room and with any sort of just basic technical issues that you may have on Zoom. And if you are on camera, go ahead and wave because we are on Facebook Live, streaming right now. So I'll go ahead and get us started. So welcome, everybody. Good afternoon. Good evening. Good morning from wherever you may be joining us. Please go ahead and get ready by settling in with whatever you need to be fully present for this talk. For those of us joining us on Facebook Live, you may want something to take notes with. My name is pronounced Linet. I'm from the Unconscious Bias Project and I'm joined today by Assistant Professor Ari Eason. And both her pronouns are she/hers. In today's talk, we will dive into erasure of Native Americans and our current cultural narrative, and what we can do about it. So before we get into the good stuff, I do want to acknowledge that UBP is based in the Bay Area on unceded ancestral homeland belonging to the Ramaytush and Muwekma Ohlone people, some of whom speak the language Chocheno. And in lieu of a more in-depth land acknowledgement, we'd really like to encourage everybody to learn a little bit more about the Ohlone people. And also check out the Shuumi Land Tax, which is a very easy way to support the nations whose land we are on, much like we would pay California state taxes. So for this session that we have today, please try to remove distractions from your work area, including other windows so you can get the most out of today, as we will be covering quite a bit of ground, we're going to use the chat tool at the bottom of your screen, as well. You may want a pen and paper or some other writing implement to write your ideas on. If at any point you have a question or comment, please direct it to me through direct message or in the chat and we'll try to address it at the end of the talk. So you will notice that we have a poll up. So please go ahead and take a moment to fill the poll. In the meantime, Ari, would you like to introduce yourself?

Ari 04:35

Um, thank you so much. Linet. So my name is Dr. Ari Eason and I'm an assistant professor of psychology at UC Berkeley. I identify as a Black woman and I grew up in a predominantly middle-class Black community in Los Angeles, California with my mom and grandparents. Overall, in my work, some of what you'll hear about today, I study infants, children and adults to unpack how the cultural system in which we live shape our thoughts and behaviors towards the members of different social groups, and how these perceptions throughout development can serve to reinforce the status quo, and subsequently what we can do to make a more just and equitable society. So here you'll see me, infancy to adulthood.

Linet 05:22

And hi everybody, my name is Linet, again, I am co-Executive Director and co-founder of the Unconscious Bias Project. I identify as a white-presenting Latina scientist from Columbia. I have mixed indigenous, possibly Chicha, African and European descent. And my path through science and academic school systems led me to the work I do now as a diversity, equity and inclusion consultant. So today, we'll talk about erasure of Native Americans and our cultural narrative. And then we'll work on tools to help reduce bias and intervene in moments of bias. Plus, we'll have time for Q&A at the end. So before we start, let's take a few deep breaths together. And take a second to type into the chat or share with us in the comments on Facebook Live. What are your intentions for today's talk? Give you a few, like 30 seconds to consider. What is your intention? Or what would you like to get out of today's talk. And that's my neighbor's dog. Hey, thank you for sharing some in the chat and direct messaging to me. So people are looking to learn to speak with folks that are different and being honest, and how to talk about this issue. Thank you for sharing. So briefly, our guidelines for today are as follows. We want to maintain openness. So keep an open mind to what you're going to hear from us as speakers, but also from each other in the chat of participation. We will ask folks to volunteer answers a few times in the chat. And for folks on Facebook Live. Go ahead and please enter your responses in the comments. We are excited to hear from you. Self-care if you need to eat take a break turn off camera, please do so. And with that, let's talk about the poll results. Ari.

Ari 07:43

Oh, okay. Can you reveal the poll results?

Linet 07:49

Oh, can you share results? There we go.

Ari 07:54

So, as expected, what you'll see from this question, really the question, joining us is what percentage of our population identifies as Native American? And I mean, I'm actually somewhat surprised by how accurate our participants are today. So it turns out the correct answer is about 2% of US society today. According to the last census. I identify as native. But one of the things that we actually know is if you ask more than just the people who are here today, a lot of people actually underestimate the number of individuals who identify as native and even the latest US Census count, which counted the most native people that we've ever had. Since we started doing the census, it's estimated to be a gross underestimate as well. But to help put 2% into context, there's also many other social groups that we don't realize are of similar size that we readily recognize in mainstream US context as contemporary peoples. So for example, we know that about 2% of US society today identifies as Jewish, I'm not sure most people actually recognize that the population of Jewish people and native people is pretty equivalent. But even you all didn't fall into I think, what was the expected trap? The question really becomes in thinking about this, what leads to the ratio of native peoples and the experiences of native peoples from contemporary contexts, and what can we do about it? Okay, so, we know that Native American presence in US society, however, only in limited and narrow ways. So we see Native people represented as mascots, in holiday celebrations, and even in the appropriation of religious and spiritual practices. However, many examples rely on sterilized versions of history. So if we take Columbus Day, which we're going to talk more about later on, as an example, we learned that he came over and discovered the Americas. But what's often left out is that there are grave atrocities that he committed against indigenous peoples, particularly the indigenous peoples of Hispaniola, right. And we see this over and over again, across the narratives. In Thanksgiving, right, we talked about how it was about this moment of coming together for the pilgrims and the indigenous peoples. And that's not really the history of Thanksgiving. There are some beautiful kinds of written accounts of Thanksgiving as a holiday actually being about a series of feasts and celebrations after the genocide of native peoples, and how often these happened. And really, that at the end of the day, they said, “Well, this is happening a little too frequently, maybe we could should consolidate it into one holiday, right?” So we see this kind of idea of native peoples looming large in our collective imagination, but they're not really these accurate representations. Okay. Understanding how Native people are impacted and how we are impacted as nonnative people by these representations is really critical. And what our science knows is that how groups are represented, has tremendous impact for understanding well-being. for understanding prejudice, bias, and inequality. So some experimental research actually shows that these neural representations of native people such as mascots are through the lens of negative stereotypes has implications for Native students in terms of lowering a sense, lowering their sense of self-esteem, in terms of lowering a sense of future aspirations, like what they hope they can accomplish with the future, right, as well as how positively they feel about being a member of their group. Right. So we know that these representations matter. Okay. And so despite the clear negative implications of the real available representations, or lack thereof, of native peoples, and for example, the massive protests against the use of native mascots, that suggests that native people were that demonstrate that native people object to these limited and narrow representations and sterilized versions of history, why we continue to hold on to the representations is really of critical importance, right? Like, why do we, as nonnative people continue to say that it's okay to use and proliferate, this type of imagery? I mean, today, what I'm going to make the case for, is the idea that what's left out is just as important as what's there. And we have to be better at identifying what's left out so that we can build a better world. So one thing that we know is that there are little to no media representations of contemporary Native peoples. So although recent series like Rutherford Falls, or Reservation Dogs, you guys might have seen these in the last year, are starting to create real change in this domain. If you look out into the media, we find that less than point 5% of media representations portray Native Americans as contemporary people. And in fact, you can try this for yourself. If you google image search, say African American, white American or Asian American, what you'll find is largely contemporary photos of people, right. But if you do the same thing, and Google Native Americans, you'll get something much different. So this is actually an example of the Google image results for Native people when you google Native Americans. And so a recent analysis actually revealed that less than 5% of the first 100 images on Google or Bing image search for Native American portray contemporary Native peoples. Instead, you get these kind of old antiquated photos of the group as though native peoples don't continue to exist today. If you dig a little deeper into the media, what we know is that almost 50% of people when asked to report rarely or never engaging with information about contemporary Native peoples, and this lack of representation has consequences. Again, if you ask people some really basic, like a question of can they name a famous native living Native American, about 80% of people can't bring a single person to mind right? And this kind of omission is even further than this, than media. If you look at school curricula, right, particularly 50 states, our academic standards, right, 87% portray natives in a pre-1900s context. So when you ask people basic information about contemporary Native peoples, almost half the time people respond, I don't know. Further, if you look at mascot representations, which are unfortunately one of the most prevalent ways that native people are represented or, dare I say, caricatured. This also perpetuates inaccuracies, right, so native mascots homogenize and dehumanize native peoples. And indeed, the majority depict native peoples as historical figures and antiquated costumery. And actually, most actually depict native people from the plains region, despite the fact that there are more than 576 sorry, the numbers are always changing, or it's been changing recently, there are more than 576 distinct native tribes across the United States. Okay. And finally, if I turn the eye to my own field, right, my own scientific discipline, which studies the nature of prejudice, bias, and discrimination, we've produced more than 40,000 publications on prejudice, bias, and discrimination. But if you actually look at what we're putting out, less than five - less than point 5%, so half of 1% - actually mentioned native peoples. And only point 2% include Native participants. And this is of critical importance because my field helps to understand what are people's experiences, and our scientific discipline helps people see that the stories that people are telling, the experiences that people are putting out there are legitimate, even though they're legitimate without the scientific backing, it carries power, right. And so what we know from this is that as a consequence of our field, not even talking about native experience within this domain, right, people actually minimize native people's experiences with racism and discrimination. So more than 75% of native people report experiencing racism or discrimination. But if you ask nonnative people, only 34% of Americans or nonnative Native Americans, non-Native American Americans believe that natives experienced discrimination, right. So there's a huge chasm between natives' experiences, and what people think they actually experience. Right? So from this data alone, it's pretty clear that native peoples are omitted from numerous consequential domains in contemporary society. So why does this all matter? Our research shows that when people don't see natives as contemporary peoples, they overlook and fail to see them as fully human. Right? We overlook the experiences of racism, and therefore, we're less likely to support policies aimed at rectifying the inequalities that native people face. Right? We know that justice is not zero-sum, working to improve the outcomes for one group doesn't preclude advocating for justice for other groups. But it's important that we actually see what needs to change in order to do that advocating and make those changes. So without acknowledging native peoples' experiences, both historically and contemporarily, particularly with racism, and discrimination, how might we explain the vast inequalities that we see across group lines? So with that, I want to provide you an example that I think makes visible of how we as a society maintain the ratio of native peoples and how we can have and continue to need to do something different. So I want to share with you one narrative that we have out in the world. So the first one is an example from Columbus Day. And here's a quote that I'm going to share with you. “On this day, we embrace the same optimism that led Christopher Columbus to discover the New World, we inherit that optimism along with the legacy of American heroes who blazed the trails, settled the continent, tamed the wilderness, and built the single greatest nation that has ever been seen.” Okay. So this is one narrative that we have about the world around us. But in contrast, I want to put in a second narrative that's very similar. And but take some like that is similar in that it focuses on a similar day, right? But it's gonna give you something very different. So here, the quote is “Our country was conceived on a promise of equality and opportunity for all people, a promise that despite the extraordinary progress we have made through the years we have never fully lived up to. That is especially true when it comes to upholding the rights and dignity of indigenous people who were here long before colonization of the Americas began. Today, we recognize indigenous peoples' resilience and strength, as well as the immeasurable positive impact that they have made on every aspect of US society.” Okay. So think about these two narratives, and think about what it might feel like to grow up in a world where you only hear the first narrative, right? Or to grow up in a world where you only hear the second narrative. What might you take away? Right? Okay. So, here's what I think can you take away? Well, that first narrative on Columbus Day, when I was young, this was actually the narrative that was predominant throughout the United States, right, we learned about Christopher Columbus, we had this really cute rhyme and 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue, we learned that he set out to find a sea route to India for spices, and that he discovered America, right. But from this narrative, what you might take away is that Columbus was brave, and that he was really pretty simple, right? If he was just out here searching for new things. And also, from that first narrative, what you might take away is that native peoples and their experiences really aren't worthy of consideration. Right? It was about Columbus being brave, it was about him discovering something. I mean, you might even go so far as to say the idea of discovery right, perpetuates this notion that indigenous peoples or that anybody wasn't already in the Americas, right? And then that the narrative goes on to talk about like tamed the wilderness, as though the people who were already there, if you acknowledge their existence at all, were somehow less than human or warrant civil, right. But from that narrative, you might never recognize the fact that Columbus didn't discover America, right? People already lived there. And you might never know that he was one of the most brutal colonizers in recorded history. And some people like to say, “well, you know, you should be judged by the standards of the time.” Well, even if you take that really stringent, high level, it turns out that the people of the time actually thought Columbus himself was a little bit too brutal, and he was jailed for his atrocities against Native peoples, right? So you might not ever see the brutality and the lasting consequences. But in contrast, if you grew up with a narrative that was more like that second one that I told you about, right, that's really captured by Indigenous Peoples Day, you might recognize that colonization was an atrocious process, and that it's continuing today to impact the lives of native peoples, you might recognize that native peoples and their experiences matter, right, the statement, openly discuss the ways in which our government has perpetuated and discrimination and enacted policies that negatively impact Native people, including genocide. Right? And you might also see the act, especially with that last sentence, that native people are contemporary, right, that they still exist today and that they're contributing to US society. Right? Okay. So you might actually come to understand that at the heart of these two holidays, right, Columbus Day on one side, and Indigenous Peoples Day on the other, you might come to recognize why narratives are so important. While the second narrative covers important but difficult truths and experiences, it's nonetheless a necessary part of moving forward and creating a more equitable society. Right. And what we know is that, despite the fact that, you know, Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492, was what I grew up with, that the narrative is changing, right? Indigenous Peoples Day is something that is being more celebrated across the United States. But there's still a ways to go when it comes to changing narratives, particularly narratives that erase native peoples. So as of 2019, only nine states actually celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day in lieu of Columbus Day. But Indigenous Peoples Day is really a holiday that serves as an acknowledgment of the legacy of colonialism and honors the experiences past and present. Of contemporary, of indigenous peoples, okay. But one of the things that we know and actually, Berkeley, the city of Berkeley was actually the first locality to study, sorry, the first locality to adopt Indigenous Peoples Day, to celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day. So a little bit of history here. But you know, importantly, this change is growing. And if you're wondering where I got these two narratives from, that first narrative, I didn't make up that quote, right, it was actually the quote from the 2020 presidential proclamation on Columbus Day given by then President Trump. But one year later, in 2021, the second narrative was the part of the proclamation given on the first-ever recognized Indigenous Peoples Day by President Biden. So you can see that whole huge shift in narrative in one year. But you know, you can imagine what would happen if you're continually exposed, how you have come up with a really different understanding of what the world looks like what people's experiences are, and what needs to change for the future. So in summary, really, as I think this, that kind of set of examples and contrast really starts to point out, is that the modern form of bias against Native peoples is actually the omission of contemporary representations, right, the fact that we as a society, right, native people have existence today, right. And we also know that social change requires infusing the broader cultural context with more accurate representations, right. And we know that native peoples and communities are leveraging this change. It, the mission is that - many people don't see or choose not to see what's right in front of them, right. Native people are putting out representations of how they want to be seen how they want to be understood, and mainstream society needs to take this up, right, we need to rewrite the dominant narrative and undo many of the perceptions held by nonnative people, which are holding native peoples back. Right. So it's really not just about individuals. It's about a culture that systematically omits the group. And so I want to show you some examples in contemporary society today about Native people. And showing that there, there's these bountiful examples of them in contemporary spaces. So here is an example of tribal youth who are working to bring Indigenous Peoples Day to their state, there was a whole report written about how to get different localities to potentially adopt Indigenous Peoples Day in lieu of Columbus Day, right. And in this case, it was led by the youth. Right? We also can think of, you know, in thinking about those Google images that we saw, well, in 2012, this is some work by Matika Wilbur, a Swinomish and Tulalip photographer that launched Project 562. At the time, there were 562 federally recognized tribes, and she aimed to photograph members of all 562 tribes, how they wanted to be seen and represented. So here's some images along that. Right. We also have prominent examples of Native American scientists, right? From both the past and today. If we look at political figures, there are so many, and the numbers are only growing at both the local and the national level. And finally, if we look within Hollywood, right, we already mentioned some of these, the proliferation of shows that center native peoplesd experiences or the incorporation of native storylines into prominent shows, and fashion. So today, I think that this just gives you a little bit of a snapshot. To bring us back to the idea that what's left out is as important as what's there, we have to take time to realize what is left out so we can really start making steps towards change. So now I want to transition us towards Linet and think about what can you do?

Linet 29:45

Thank you, Ari. So I'd like to tell you a little bit more about personal and interpersonal interventions we can use to avoid falling into these pitfalls of stereotypes and erasure of folks like Native Americans. So, before we get to that, I do want to lay the groundwork through a few basics. So first off, what is bias in the first place? So we can define bias as prejudice in favor of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way that we consider to be unfair. And unconscious or implicit bias is bias that you have, even though you don't consciously agree with it, or even though it's there. And at the Unconscious Bias Project, we see bias as being reinforced through stereotypes, which are oversimplified ideas about a particular type of person or group. And stereotypes are everywhere, as there's been some active discussion in the chat. There are stereotypes in books and movies and conversations we hear even in the products we buy. So before stereotypes even lead to bias, stereotypes by themselves are damaging, because of significant damage to the mental and physical health of the person or people being stereotyped. Now, remember my introduction about ourselves at the outset, I'm not just a woman, I'm Latina. And I'm not just a Latinx woman, I have both indigenous ancestry and I am white-presenting. And I'm not just white-presenting, I am also a mom, and all of my identities come to play together and the biases that others may have in favor or against. Sorry, we're getting a little distracted here, okay. And all of these different identities that I have do come into play when others might have biases in favor or against these identities that I have. And that intersectionality is also true for many Native Americans and indigenous peoples. And that's what I will talk about. So first, I'll cover a couple of common stereotypes, they may intersect with Native American identities and stereotypes. And don't worry, After naming these stereotypes, we'll do work in a bit to counter them. Alright, let me get us set up for our first activity. So for those of us that are joining us in Zoom, please use the chat to type a one for how many of these experiences you've seen, or experienced yourself, or maybe even thought of before. And for those of us joining on Facebook Live, go ahead and tell us how many of these stereotypes you may have seen. So men as breadwinners, and women as caregivers, men as breadwinners, and women as caregivers. How many people have heard of this one?

Linet 32:42

You know, at least for me, it is very international. Okay, good. Yeah. Lots of people have. Okay, how about the stereotype of Native Americans as brave warriors? Native Americans as brave warriors. I feel like I've seen this in every single movie or TV show that has ever had a Native American until recently. Okay, how about Black people as loud? Yeah, exactly. Yeah. Well, so lots of people are typing ones in the chat. There's a very, very common stereotype. How about Asian people as good at math? Who's heard of that one Asian people is good at math, because even positive stereotypes can be harmful. All right. Last one, transgender people as outcasts, who has seen transgender people being portrayed as outcasts. Yeah, lots of folks responding into the chat. Thank you for chiming in. So don't worry, we're not going to let these stereotypes sit and just continue to be harmful, we are going to do some work to undo them. And the stereotypes that are on this slide are what are often buried in our minds that cause us and others to think and act in ways that we would not be proud of whether that's intentional or unintentional. And stereotypes can add up. So if you have multiple identities, all of those stereotypes can add up on you. For example, if you're a Black Native American transgender woman, you would be subjected to a lot more stereotyping. And the effects of these stereotypes can be seen all the way from how six-year-olds see themselves, to whether teachers recommend students to math and science or language and art schools to whether or not we get hired or offered a good hiring package, or whether or not we get promoted at work and how we're treated at work. And these barriers keep some groups underrepresented in certain careers like science and math and reinforce pre-existing stereotypes of who belongs in those careers and in leadership positions in those careers, which creates vicious cycles of exclusion. And this applies to everybody, including Native Americans. Remember that statistic that Ari you mentioned earlier about how 75% of Native Americans report experiencing microaggressions. Well, that impact can happen here in careers, and it can be felt in other systems as well. And even though some of these sources of these biases are really rooted in past genocide, slavery and colonialism, the effect of these historic and current biases and inequitable systems are still very real, and really do impact us today. Sometimes in ways that can be much more subtle. For example, I do benefit from being white-presenting, but I don't benefit from being Latinx, a woman, or being a mom. And benefit comes with impact and financial, health care, and criminal justice systems, where I can move much easier than say, my sibling or grandma who do have much more melanated skin and curlier hair. All right, well, thoughts are the first line of defense when confronting bias. So we're going to teach you one of our five practical techniques that can help you target your own unconscious bias and decrease it, that you can start applying today. But before we start training, we need to cover some prerequisites. In order for these techniques to work for you, you need to be motivated to overcome your own bias, which is why we made sure everybody today has the basics and the data to know why we need to change. Next, you need to take steps to become aware of your bias and why it exists. There are lots of ways to do this, like taking an implicit association test at Harvard's Project Implicit website. Third, you need to learn to detect the subtle influence of stereotypes, which helps you know when it is a good time to act. And fourth, you have to practice these strategies to reduce your bias so that you know what to do in the moment. And yes, I definitely emphasize practice, because without it, there will be no change. Alright, so let's learn and practice together. And I'll give you a brief overview of our five strategies. And I will tell you a little bit more about the one we're going to use today. So our five strategies are stereotype replacement, individuation instead of generalization, perspective, taking counter stereotypic examples, and increasing opportunities for connection. And today, we're going to fully work through stereotype replacement. Alright, so everybody take a look at this picture. And capture it in your mind. What was your first reaction? What did you assume about the people in this picture? Did you assume that they were undergrads interns? Or are they leaders? Are they straight? Were queer? Are they indigenous or not? Are they able-bodied or not? Do you think they're communicating well, or poorly? So when I first saw this picture, my immediate thought was “young intern.” And that's my bias. And once you've acknowledged that your own biases are informing how you see somebody, you can choose to replace any biased aspect of your gut reaction with different less your typical thoughts. And this is what we call stereotype replacement. The idea is to consciously recognize that a thought you just had stemmed from a stereotype. And instead of leaving that bias buried in your unconscious, bring it up to the surface and replace it. In this case, I can choose to recognize my biased reaction. And think “lab leader, Professor, maybe startup owner,” right. Okay, so now we're going to practice this together. So get your creative hats on and flex out your fingers that you will use for some typing, we're going to do some quick-fire replacing stereotypes practice. And what I'm going to do is I'm going to read off the same stereotypes that we talked about in the beginning. And I want each of you to take about 10 seconds to write as many stereotype replacements as you can into the chat. Okay. And for folks joining us on Facebook Live, go ahead and type in your stereotype replacements into the comments. All right, I'll read off each one and please remember to enter in as many different serotype replacements as you can.

Alright, men as breadwinners, what could men be other than breadwinners? Raising children, men as caregivers? Oh and you have a comment about stereotypes also hurting other people in the audience. That's true. That's exactly right. Okay, partners, men as homemakers, as fathers great. Okay, you're getting the hang of this All right, how about women, women as caregivers? What could woman be? That has nothing to do with caregiving? Women as CEO is a great first start. Women as breadwinners. breadwinners? Yes. The boss, [I] like that. Okay. Leaders. Excellent. Writers. Yes. In Charge, yes. Anything at all? Exactly. Astronauts. Yes, astronauts. Nice one. So the more specific we can get with some of these examples, the easier it'll become to replace stereotypes as you see them. Okay. Next one. Native Americans as brave warriors. What could Native Americans be that have nothing to do with being a brave warrior? What could Native Americans be? My good friend, teachers, doctors, homemakers, professors, lovers, caring neighbors, CEOs. Yes. Artists. Perfect. Really good job. Okay. Black people as loud. What could Black people be other than the stereotype of being loud? What are they allowed to be what characteristics could they have to be a great friend, engineers? Leaders? I think I missed one, writers, caregivers, sports people, astronauts, president, yes. Social engineers. Beautiful. Okay, good. You’re really getting the hang of it now. All right. How about those positive stereotypes that you're also harmful? Asian people as good at math. Oh, when last one for Black people. Black people could be scientists. Great. Okay, Asian people as good at math. What can Asian be people be? That has nothing to do with their math skills. strong and loud. artists, actors, athletes, my friend. Yes, it's so it's actually really great technique is to conjure up your friend whenever you see a stereotype of a group that they belong to. That's a very effective way. Good writers, CEOs. Yes. Great punks. Yes. Some people can be fine. Okay, singers diapers. Okay. I love this. I love this. All right. Last example, transgender people as outcasts. What could transgender people be? Has nothing to do with being outcasts. Leaders, politicians, artists. Yes. Preschool teachers. Yes. Friendly heroes winning Jeopardy. Okay, you guessed one of my examples that I stored here. In case people were getting stuck. Yeah. Okay, great. So, to summarize this little subsection, biased thoughts are a habit that can be broken. Well, mostly, you can never quite be cured of unconscious bias. But over time, strategies to reduce bias become habits themselves, and it will get easier to squash unconscious bias when it comes up again.

Okay, so we're going to shift away from our internal struggles and dive into how we can respond to bias in our environment. We've been working with an amazing cartoonist, Teresa Oborne, to illustrate - quite literally - what bias looks like in day-to-day interactions ,and how we can respond. Excuse me. So how many of you have heard this one before? She's really smart, but I wish he wasn't so bossy. can give me a one in the chat. If you've heard this one before. She's really smart, but I wish she wasn't so bossy. And people on Facebook Live, give us a little heart reaction. Okay, I see a few people. Okay, I have definitely seen this one. And to tell the truth, I may have thought of it one or two times. Remember, we are all biased and we can be biased even against our own in-group. So let's identify the bias here. This cartoon showcases a very common bias against women in leadership roles. So if you're that person in the back, what are your options when someone says this to you? Well, I don't recommend labeling the person who made the comment as hey, you're sexist. Instead, we offer four simple strategies to highlight the problematic nature of the comment and encourage a change in behavior rather than getting into an argument. So our first strategy is to observe the problem. Instead of staying silent or moving on, observe that the comment was stereotypical and hurtful. Something like “Ouch, that's a bit harsh.” Or you could counter micro-aggression with micro-affection. I love that term. “I don't think she's bossy. She's a strong leader.” A positive comment like this can help weaken the negative stereotype for those around you, without being too confrontational and without derailing the conversation. Third, or bystander could also reflect the common back, which would make the speaker do the work of challenging their own assumptions. So things like, “how can we never call guys bossy?” And finally, you could simply label the stereotype that's in play. “Okay, that's reinforcing a hurtful gender stereotype, which I'm sure you didn't intend to do.” And this isn't about being passive-aggressive, just honestly reminding the other person of your shared values. So let's practice in this cartoon. Two people are at a cafe. And the woman on the right comments, you don't look indigenous to the guy on the left. This is actually a very common microaggression that indigenous people face in the US today, a close second to being told that they're “lucky to be,” quote, “Indian.” Right. So let's practice. Start by identifying the possible stereotype behind this comment. And go ahead and type it into the chat. So what is the possible stereotype or stereotypes here? We'll think about it for a few moments and go ahead and share what you think in the chat. What could be the stereotype here? What could be the bias at play here? Okay, stereotyping that all Native Americans look a certain way. Good job. He isn't wearing turquoise, for example, yes, race as a bias, assuming the person is not indigenous. Exactly. So there's at least one bias in the situation. And that is that Native American and indigenous people need to look like the speaker's image of a stereotype of indigenous people in order to be allowed to be indigenous right out. So what could an onlooker say or do to intervene in this moment? So we have our list of possible interventions here on the slides, we have observed the problem positive redirection, transfer the work or label the stereotype. So go ahead and without pressing ENTER, type into the chat. One idea of how to intervene. What could you say if you were an onlooker, or maybe a friend of this group? What could you say to intervene in this moment of bias? Go ahead and take some 30 seconds to consider how you might intervene. And you can use any one of the intervention methods listed on the slide. And you can also get some get excited press ENTER early, that's okay. Or you could use your own method of intervention or you could put yourself in the role of the person that's receiving the comment. So these intervention strategies work if you are a bystander, but they also work if they are directed at you. Okay, go ahead and press enter. Okay, good. Okay. Let me get all these okay. “What does an indigenous person look like? It sounds like you think indigenous people look a certain way.” Can you tell me more? “What do you think an indigenous person looks like Native Americans still look a certain way?” “I guess white individuals can be Jewish, Russian, but may not look that way.” “I would love to know more about you.” Is that a good or bad thing? Oh, “is that a good or bad thing?” Yeah, that's true. “Native Americans come from many tribes and look very different from each other.” Great. So here are some examples that we came up with. “My friend can look any way he wants and still be indigenous.” You could use positive redirection, of course, “he looks indigenous. He's Ohlone.” Oh, that's another great intervention. “Look beyond how I look,” great. They could transfer the work like many of you have written here. “How do you decide whether or not someone looks or is indigenous enough?” And finally, you can label the stereotype. “Questioning someone's identity based on stereotypical looks reinforces those harmful stereotypes.” So excellent job, everybody on those interventions. So with that, let's wrap our actions. So yes, unconscious bias is a real problem. And yes, ways to reduce unconscious bias are real too. So no matter what roles we play in different situations, or maybe in different organizations, we each have options for what to say in the moment when we see or experience unconscious bias, and what policies we can advocate for that can guide everyone towards less bias. And even though most of us do have unconscious bias, those biases don't own us. With dedication, we can continue to practice breaking the bias habit and become closer to the people around us, and really get closer to the people that we actually want to be. So Ari, I'm going to hand it over to you to wrap up our session for today.

Ari 50:34

Thank you so much for all those amazing activities and information. So what are our general take-homes, I think they fall into three large buckets, three buckets. So first, what we have to say is that we need to learn, it's really important to seek out information, the information that's in front of us every day might not be the whole picture. So we have to be active in finding out more particularly, finding out more about groups that are omitted, right. So what can you do here are some links that you could follow just as first steps, right? The National Museum of the American Indian has a beautiful website that you can peruse through the exhibits. There are articles about the first Indigenous Peoples Day and articles about why the US still celebrates Columbus Day, written for broad audiences. You can also learn about your local tribes, there's this beautiful visualization and map that talks about the tribes that are from and still occupy the areas that all of us live in, across the United States. Okay, so after you do some learning, you also have to be comfortable with discomfort. So the reality is of history can be really hard to accept and to sit with, right, if we think back to that narrative from Indigenous Peoples Day that talks openly about the atrocities, and the genocide of native peoples, for example, that can be really hard to stomach and handle, especially when it comes to thinking about what is all of our roles, and both historically and today. But it's important that we sit with that even in those difficult times, knowing and acknowledging the truth is necessary for change. And I think one thing that really helps is remembering that it's not about you, while we are not necessarily responsible for the past, we are responsible for the future. And finally, as Linet beautifully laid out for us, we can act. So one thing that's important is pushing against the omission of native histories and perspectives, right, and push against the omission of contemporary Native peoples and experiences when we talk about prejudice, bias, and discrimination. Are we talking about Native peoples in this context? When we're talking about, what needs to change? Are we remembering to include Native peoples and their voices in the conversation? And remember, it's not just about what you say, it's about what you do. So what can we actually do in that in the form of acting? Right? When we have the chance, right, we can help get other people on board, right, and gather the courage to act. So what does that look like intervening in those moments of bias when it comes up in your own mind? Right, kind of interrupting that thought process? And saying, “Hmm, is this what we should be thinking?” Or why? “Why am I thinking this?” Right? intervening in moments of bias when you see them occur? Right? We already had some beautiful practice with that across numerous domains. And what does it also look like advocating for policies curricula change and legislation that includes native peoples, and counters systems of oppression. And it also looks like using your power to vote. These are just some examples. And finally, but of course, this list is not exhaustive. You can also think about supporting the indigenous nations in your area, by finding out what they are, what they want, and how they could use your support. Right. This is, this links fundamentally back to that “listen and learn” piece. So in the Bay Area, there's many different options. So you can help the Muwekma Ohlone tribe become federally recognized, you can contribute to and share the Shuumi Land Tax right? You can contribute to the Ramaytush Association, right? These are all tribes that are from here in this bay area. Okay. And so you one part of acting is listening to what these groups want and working At use your power to help them advocate as they see fit. Right. And beyond the Bay Area, there's also across the United States. So you can help disseminate educational information about Native peoples by native peoples, right? You can also advocate to change the name. So the use of native mascots, even though it's decreasing over time, is still quite prominent, right? So there have been calls for the Kansas City Chiefs, for example, to change the name, these are just various ways that you can support. So with that, I want to say thank you and give the floor back to Linet.

Linet 55:42

Thank you, sorry for bringing us home there. So we'll get to your questions in just a sec. I do want to thank Dr. Cordero, from the Association of Ramaytush Ohlone, for his guidance on action items to share with you also to Nerd Night SF and our fabulous anonymous donor for sponsoring this event, round of applause. And a thank you for buddies at Nerd Night, San Francisco and Science at Cal for partnering with us to share this event, and to the Bay Area Science Festival for inviting us to speak. As for us, I'd like to tell you how you could continue your learning in action. And I will type all of these links into the chat. And you will also get them our list of references and action items that we shared in your handout after this talk. So if you liked what you heard today, there are two ways to support us. You can donate through the link that I will drop in the chat shortly or refer us to your organization or friend that would benefit from working with us. We at the Unconscious Bias Project offer custom keynotes, comprehensive climate surveys and practical workshops for organizations big and small, you can just send them on over to ubproject.org. If you would like to get involved, learn more or sponsor an event like this one, you can visit our website or email me directly at linet@ubproject.org. And don't forget to follow Ari on Twitter as she continues to grow her group and study areas including narratives of queer folks, and what representational landscapes look like. So thank you so much for coming along on this journey today. And now we'll get to your questions. Oh, one final slide from the Bay Area Science Festival, there are a lot more events still going on. So be sure to check their website for more events. So I will stop share. And have us in this group setting I will unpin us see pin each person. So we can all see each other. So we can open us for questions. And I do want to say acknowledge that we had a person that was being inflammatory in the chat. And I appreciate your patience with us on working with them and asking them to please stop that behavior. So appreciate your patience there. And thank you all for your fantastic participation. Okay, so now we're open for questions, any questions that you have on the material that we shared or any questions for us specifically, we are your experts. And we're here to answer your questions. And if you'd like to ask a private question, you can direct message me. “Are Native Hawaiians considered Native American,” Ari, you would you like to take that one?

Ari 58:46

Yeah, so that's a really good question. I think the data… well, it's a complicated question. In the straightforward, easy answer is no. They're not Native American as we would consider them, but they are native peoples. So if we remember the fact that native and indigenous peoples are a diverse group, Native Hawaiians are indigenous peoples, they’re indigenous Hawaiian, but their relationship to the US government is a little bit different than many of the native tribes on mainland mainland us. But they do still have rights and distinctions that, you know, put them within that indigenous category that many people identify with. So even though kind of the political distinction is a little bit different from Native Americans, they still have very similar experiences that track well, that answers your question without getting super deep into the nuance there.

Linet 59:54

Thank you, Ari. It's great to have an expert to answer these questions. All right, I have a direct message. I'm asked if we work in the field of LGBTQ discrimination? Yes, we do. At the Unconscious Bias Project, we're a little different from other folks out there, and we think intersectionality is really important. So, you know, not everybody lives in a silo. And we all have intersectional identities. So we do do work, to counter anti-queer discrimination as well. And you can totally drop me an email linet@ubproject.org If you're interested in learning more. Oh, and I had a question, direct message to me way at the beginning, which is “what is white-presenting?” Which is a really good question. White-presenting just means that somebody that you might not consider that might have, you know, a different racial or ethnic background different from white appears to be white. So that is, that is me, I am white-presenting. Any other questions or maybe a take-home that you want to share with us? We're happy to take more questions. Oh, that's a good question. That was direct message to me. “What does it mean to be white?” Ari, you do you have thoughts on this? Or would you like me to say? Yeah, so it's very interesting to consider, what does “white” mean? What does “Black” mean? What does even “Latinx” or “Hispanic” mean, and really, at the crux of it is, if we think all the way back to sort of the justifications for colonialism and slavery, and genocide of multiple different people across the world, there is this structure, try not to go into much detail, a structure of white supremacy that basically made it so that there were good characteristics associated with whiteness and pale skin, and bad characteristics associated with anybody else. So that is sort of how, you know, we started these distinctions of, you know, who is permitted to have power, who is permitted to own things, or who is permitted to have justice or rule or anything like that it all sort of comes from these original frameworks. And it does, you know, impact a lot of the way that we move now even though you know, most of us we like, okay, that's totally arbitrary distinction that has absolutely no basis on anything that sort of like where it all came. And we can go further in depth into that. If you want more information, just email me. “Do you have data on how education and identification?” I'm not sure I understand the question of these biases, bias possibly could impact - Oh,” data on how learning about biases and how to counter them, how they impact society?” Is that the question? Yes, there is some data, it depends on which sector you're specifically interested in. For example, in companies that purposely diversify their leadership and are aware of, for example, majority groups in their organizations, they were able to achieve, I think, over 20% More in innovation, and a lot more, in their more competitive than their peers in the fields, etc, etc. Same for teachers, if you get teachers aware of their own biases, they're more likely to recommend students evenly to different fields that they're interested in, as opposed to, you know, shoehorning them into one section.

Ari 1:04:10

Okay, what we also know is that in the case of bias towards Native Americans, we've run a series of studies that actually look at how we can combat the lack of representations. And so by providing people say, information about Native peoples and contemporary context versus in historic context, that actually reduces bias and increases so it makes people feel more positively towards Native people. And it also increases support for policies aimed at rectifying inequality. So we've seen this in the domain that's really specific to what we presented on here.

Linet 1:05:01

Just kidding, I was totally on mute. “I'm currently doing research on the diversity of social studies curricula in public schools of America. So I was wondering if you believe that curriculum is not diverse enough? If so, why has this happened? Do any steps to any steps that students can take to encourage more diverse curricula?” There's a great resource that you shared already. Do you want to discuss that a little bit? Oh, and that's also in the link, the tiny.cc/ohbehave has all of our resources and references in there that include curricula? Ari, do you want to speak a second about that?

Ari 1:05:42

Yeah, um, so in terms of the curricula, I think there has been a number of peer reviewed articles looking at different forms of curriculum, one of them that I did talk about earlier today was that 87% of references to native peoples in our academic standards, which really sets what schools across all the states are supposed to learn, put native peoples in a pre-1900 context. If you delve a little deeper to that, it turns out that only four states I believe, mentioned native people by name, or like mentioned a native person by name, but there are a lot of states that actually are making changes. So Washington state, for example, has a, I guess, mandate, I could get the name wrong. But I think it's called since time in memoriam where they're expected to teach about local tribes and native history. Similarly, there's, in in Minnesota, they’re also making, you know, those shifts, I think what we're seeing across society is that representation is lacking in various different ways, whether it's about people's contributions to American society, whether it's about their experiences. And so we do have a ways to go in, in those respects, where you can also think about it in terms of the siloing of particularly like groups, right? So only Black people, for example, being talked about during Black History Month, as though the history of these groups aren't fundamentally a part of American history as a whole. So those are kind of some subtle shifts that can be made. Why do we think this is happening? Well, there's some theories out there that suggest again, that confronting the realities of history is really hard. It doesn't feel good to know that people in your group or that we've built a society that may not be as fair as we want it to be right, that has systematically excluded particular groups of people. And so some people are advocating for shying away from that, right? And how can we take steps to encourage a more diverse curriculum, I think we have to advocate, use our voices, use our power. I think one example that people can draw on is actually that Indigenous Peoples Day report that was made, it talks about different ways that different groups have actually gone about trying to get their locality that celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day, as opposed to Columbus Day, and it includes kind of in-depth interviews with different places who were successful in this. And I think there's similar models that could be used in terms of shifting school curriculum or making sure that people are represented accurately within these contexts.

Linet 1:08:56

Thank you, Ari, for filling that so expertly. Alright, we are over time. Thank you so much, everybody, for your great questions. Great discussion and participation. Thank you, Susanna for helping us with the chat and with the admitting people in thank you so much to share you for doing ASL interpreting. And thank you, Ari. Go, team “Oh, Behave!” You did a great job. All right. Do keep in touch with us and we'll follow up with you soon with an email with the references and the information that we presented here. Thank you so much and have a great rest of your evening or great rest of your day. Bye-bye.